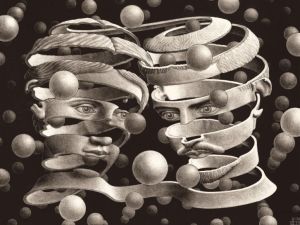

M. C. Escher. Bond of Union, 1956

To what extent are the modernist conceptions of the subject Cartesian? What of our sciences, especially the human sciences and knowledge that emerges from them? And how can we overcome these lingering Cartesian residues? Gardiner in ”The incomparable monster of solipsism’: Bakhtin and Merleau-Ponty’ explores these questions (and more). This post is an attempt to provide a brief review of this paper.

The subject, at least as far as Western metaphysics goes, is narcissist for it is shadowed by the Cartesian view which yields to a total self-determinism and total-self-grounding, Gardiner argues. Our capacities for abstract thinking are privileged at the expense of embodied dialogism. The production of knowledge according to Western metaphysics is rooted in the solitary subject contemplating an external world in a purely cognitive manner as a disembodied observer. The locus of classical modernity, is captured by the overwhelming desire for epistemological certitude and logical coherence in the desire to establish absolute certainty. In attempting to establish this lucidity and certainty; complex, multivalent and ambiguous reality is substituted with crystalline logic and conceptual rigour. Our obsession to transcribe the world into pure algorithmic language, as if the external world presents itself as a collection of inert facts, according to Gardiner, is the epitome of Cartesianism. Merleau-Ponty describes this as “A nightmare to which there is no awakening“.

It is however, important to note that the status of the human sciences has evolved considerably over the course of the enlightenment and since Popper, falsifiablity and not certitude and coherence is the hallmark of science. Descartes, with emphasis on doubt stands at the beginning of this tradition and as Ian Shapiro would argue, the locus classicus of modernity is in fact doubt, skepticism, and falsifiability.

Nonetheless, Gardiner reminds us that the Cartesian perspective, not only remains central, but also poses a threat to dialogical values and what they espouse. By seeing the world as a projection of cognitive capacities, we leave no room for recognizing otherness. Not only is the body alien to this physical subject, other selves are equally mysterious that can have no authentically dialogical relationship. It is by adopting a dialogical world view that we are able to capture the interactive nature of bodies and selves as they co-exist within a shared life world. Gardiner asserts that Bakhtin and Merleau-Ponty are in agreement that modern Western thought, Platonism being the archetypal example, is dominated by perspectives that have rejected the validity of the body and it’s lived experience in favour of theoretical constructions. The utilitarian character of modern science and technology and abstract idealist philosophy reflects this. The tradition in which arguments are framed and debated in the philosophy of mind where philosophical zombies and Martian c-fibres often take centre stage, illustrates this further.

This privileging of purely cognitive abilities results in tendencies in equating the self to subjective mental processes. This comes at a price of the viewing the subject as something abstract that dispassionately contemplates the world from afar. The Bakhtinian dialogical perspectives strongly oppose such formulations of the subject. Bakhtin insists that relation to the other requires presence of value positing consciousness and not a disinterested, objectifying gaze. Without the interactive context connecting self, other, and world, the subject slips into solipsism and loses ground for its Being and become empty.

Similarly, for Merleau-Ponty, the world is always in a Heraclitian flux, constantly transforming and becoming — not static and self-contained. Nor is our relation with others a purely cognitive affair. World and body exist in a relation of overlapping. My senses reach out to the world and respond to it, actively engaging with it. They shape and configure it just as the world at the same time reaches deep into my sensory Being. The perceptual system is not a mere mechanical apparatus that only serves representational thinking to produce refined concepts and ideas but is radically intertwined with the world itself. Self perception, according to Merleau-Ponty, is not merely cognitive but it is also corporal. As I experience the world around me, I am simultaneously an entity in the world. I can hear myself speaking.

The world is presented to me in a deformed manner. My perspective are skewed by the precise situation I occupy at a particular point in time/space, by the idiosyncrasies of my psychosocial and historical context of my existence. Since I am thrown into the world lacking intrinsic significance and I have to make the world meaningful, I am condemned to make continual value judgments and generate meanings. I can never possess the totality of the world through intellectual grasps of my environment, thus my knowledge of the experiential world is always constrained and one sided. As meaning of the world for each of us is constructed from a vantage point of our uniquely embodied viewpoint, no two individuals experience the world precisely the same way. Encounter with other selves is necessary to gain a more complete perspective on the world. I am never my own light to myself. It is through encounter with another self that I gain access to an external viewpoint through which I am able to visualize myself as a meaningful whole, a gestalt.

Gardiner argues this is how we can escape solipsism – through an apprehension of oneself in the mirror of the other, a vantage point that enables one to evaluate and assess his/her own existence and construct a coherent self-image. To be able to conceptualize myself as a meaningful whole, which is fundamental to self-individuation and self-understanding, I need additional, external perspective. By looking through the other’s soul, I vivify my exterior and make it part of the plastic pictorial world.

We need a philosophy that understands nature as a dynamic, living organism that is ‘pregnant with potentials’. As embodied subjects, we are intertwined with the world, bound up with the dynamic cycles and processes of growth and change. Insofar as our minds are incarnate and our bodies necessarily partake the physical and biological natural processes, there is an overlap of spirit and matter, subject and object, nature and culture. No break in the circuit; impossible to say where nature ends and subject begins. The self is dynamic, embodied, and creative entity that strives to attribute meaning and value to the world. We are forced to make certain choices and value judgments by Being-in-the-World to transform the world as it is given into a-world-for-me. In making the world a meaningful place, the subject actively engages with and alters its lived environment. I and other co-mingle in the ongoing event of Being. The self, as Bakhtin points out, is ‘unfinalizable’ – continually re-authored as circumstances change.

Gardiner concludes that both Merleau-Ponty and Bakhtin object to the ‘Primacy of intellectual objectivism’ taken as the model of intelligibility which forms Western philosophy from which our sciences emerge. Such objectification of the world in modernist paradigms represents a retreat from lived experience. Genuinely participative thinking and active engaging requires an engaged, embodied relation to the other and to the world at large. Our capacity for abstract cognition and representational thinking is incapable of grasping the linkage between myself and the other within the fabric of everyday social life. Hence the solipsistic consequences of subjectivistic idealism. As Bakhtin’s ‘carnal hermeneutics’ – the dialogical character of human embodiment – emphasizes, the incarnated self can only be affirmed through its relation with the other. The body is not something self-sufficient: it needs the others’ recognition and form giving activity.