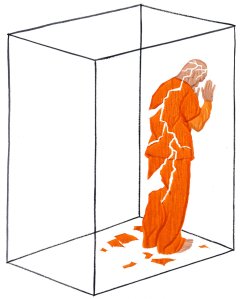

I recently came across this extremely powerful and disturbing 3 minutes video of solitary confinement. Given my dialogically informed perspective, it made me reflect (as well as initiate conversations with others ;-)) on the concepts of self, other, and world. Solitary confinement, which is the absence of dialogical relationship with others, seems to have a devastating effect on one’s sense of self and this video is an unerring illustration.

I recently came across this extremely powerful and disturbing 3 minutes video of solitary confinement. Given my dialogically informed perspective, it made me reflect (as well as initiate conversations with others ;-)) on the concepts of self, other, and world. Solitary confinement, which is the absence of dialogical relationship with others, seems to have a devastating effect on one’s sense of self and this video is an unerring illustration.

Solitary confinement is the complete isolation of prisoners from others or significantly reduced intersubjective contact with others or technically speaking, physical isolation for 22 to 24 hours per day. Solitary confinement is often referred as “Administrative segregation” in prisons. It is a common practice across the globe. In the US alone there are 80,000 to 100,000 inmates held in solitary confinements everyday. Similarly in Canada, “On any given day, there are 850 offenders (about 5.6% of the prison population) in solitary confinement. Some of these inmates have been isolated for more than four months. Many are young. Many have serious mental health problems.”

I don’t think there can be much disagreement regarding the disturbed state of most of the prisoners in the video. Solitary confinement deprives us of intersubjective contact with others which is imperative for constructing and sustaining our sense of self. Alexis de Tocqueville and Charles Dickens have described the prisoner in isolated cells as “buried alive” and subjected to “immense amount of torture and agony” through a “slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain”. Looking at solitary confinement from a phenomenological perspective, Gallagher (2014), has identified a long list of substantial negative health effects associated with solitary confinement:

“anxiety, fatigue, confusion, paranoia, depression, hallucinations, headaches, insomnia, trembling, apathy, stomach and muscle pains, oversensitivity to stimuli, feelings of inadequacy, inferiority, withdrawal, isolation, rage, anger, and aggression, difficulty in concentrating, dizziness, distortion of the sense of time, severe boredom, and impaired memory.”

Solitary confinement can alter or eradicate sense of self. “The person subjected to solitary confinement risks losing her self and disappearing into a non-existence”. Nonetheless, such effects of solitary confinement are often understated perhaps due to our individualistic perception of self and our tendency to underestimate the importance of others as constituents of self. In fact, as Foucault in Discipline and Punish reminds us, the original purposes of solitary confinement, was as a positive instrument for reform. Solitary confinements were thought to rehabilitate the prisoner as a social and moral individual through reflection in isolation – a way for the prisoner to reflect on their crimes and return into his inner ‘true’ self. Given time to introspect in a solitary confinement, the prisoner was expected to turn their thoughts inward, repent their crimes, and eventually return to society as a morally cleansed citizen.

“Thrown into solitude, the convict reflects. Placed alone in the presence of his crime, he learns to hate it, and, if his soul is not yet blunted by evil, it is in isolation that remorse will come to assail him”

(Tocqueville in Foucault 1979: 237)

At the centre of this viewpoint is an underlying assumption which views the individual as something that exists and is capable of reasoning and functioning in isolation from others – a notion of the individual that is self-sufficient and self-contained where the necessarily interrelatedness of self, other, and world is overlooked. For philosophers such as Gardiner, this individualistic notion of the self is something we have adopted from the Western Christian notion of the soul through Cartesian-inspired philosophies. Contrary to this notion of solitary (which is built upon individualistic assumptions) as a means to come back to the inner self, deprived from contact and interaction with others, the very core of our existence is threatened.

‘‘Just as the body is formed initially in the mother’s womb (body), a person’s consciousness awakens wrapped in another consciousness … Individuality is created by and through others and the Other is part of the self.”

(Bakhtin, 1990)

Coming back to my brief musing, the fact that our sense of self seems to erode when we are deprived of interaction with others reinforces the Bakhtinian dialogical viewpoint that self and others co-develop and are two sides of the same coin. It is through our dialogical and embodied interactions with others that we are able to form and sustain a sense of coherent self. Others are essentially involved at all social and individual lived experiences. Through our encounters with others, we are able to evaluate and assess our own existence. Depriving the person of ‘others’ by subjecting them to solitary confinement, denies that essential additioal external perspective, the means by which a coherent self-image is maintained and the person risks losing the ‘self’ and disappearing into a non-existence.